On a low ridge above the River Deben in Suffolk lie a series of grassy mounds. For centuries they were just part of the landscape, known locally as “the Hoo”.

In 1939, on the eve of war, a dig into one of these mounds revealed one of the greatest archaeological finds in Britain…the Sutton Hoo ship burial.

Start of the Dig.

The landowner, Edith Pretty, had long been curious about the mounds on her estate. She asked local archaeologist Basil Brown to investigate. Working with little more than spades, Brown uncovered the outline of a huge wooden ship, buried beneath a mound more than 1,300 years old.

The vessel itself had rotted away, but the iron rivets remained in place, leaving a perfect impression in the sandy soil of a warship nearly 90 feet long.

At the centre of the ship was a burial chamber. Inside, the archaeologists found a trove of objects…weapons, armour, silverware, and ornaments…that spoke of immense wealth and power.

The Finds

Chief among them was a remarkable iron helmet, decorated with tinned bronze panels showing warriors, animals, and mythical beasts. Alongside it lay a coat of mail, a sword with a jewelled hilt, spears, and a great shield with a metal boss.

There were also Byzantine silver dishes, drinking horns, a lyre, and even fragments of textiles woven with gold.

The burial has been dated to the early 7th century, a period when several kingdoms vied for dominance in Anglo-Saxon England.

Scholars generally link it to the East Anglian royal house, and some believe the man honoured there was King Rædwald, who died around AD 624–625. Rædwald is mentioned by Bede as a powerful ruler who straddled the line between Christianity and the old pagan gods.

If it was indeed his tomb, Sutton Hoo provides a direct connection to one of the first English kings.

Unique

What makes Sutton Hoo extraordinary is the light it sheds on a time often thought of as dark and poor. The burial goods reveal a culture of artistry, craftsmanship, and international links.

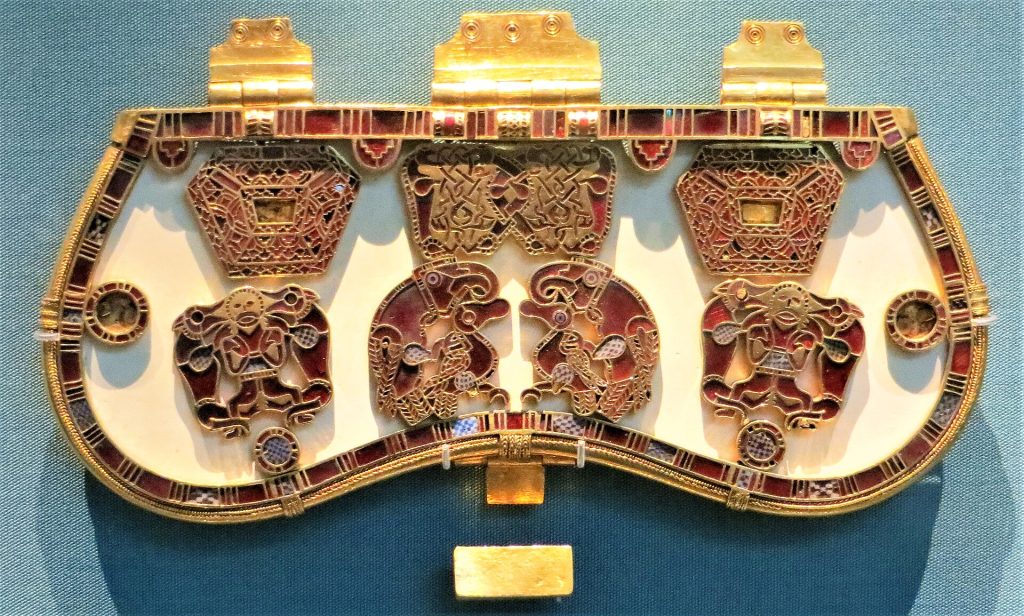

The gold belt buckle, shoulder clasps, and purse lid display intricate cloisonné work with garnets imported from as far away as India or Sri Lanka.

The silver bowls came from the Eastern Mediterranean, showing trade and gift-exchange networks that stretched across Europe. Far from being isolated, early Anglo-Saxon England was plugged into a wider world.

The discovery also changed our view of Anglo-Saxon warfare and kingship. The helmet, now one of the best-known objects in the British Museum, shows both practical protection and symbolic display.

Combined with the sword and shield, it marked the burial as that of a warrior leader. Yet the inclusion of feasting gear, music, and fine textiles suggests that power was as much about ceremony, generosity, and religious authority as about fighting.

War Stops Play

War cut short the first excavation. In September 1939, with the outbreak of conflict, the finds were hurriedly shipped to London and stored in the Underground for safety during the Blitz.

Only after the war did scholars return to study them in detail. Since then, Sutton Hoo has continued to yield new information.

Later digs revealed more burials, including some grisly executions around the edges of the site, hinting at its long-lasting role as a place of power and judgement.

Today visitors to Sutton Hoo can see the burial mounds much as Edith Pretty did, though the great ship lies beneath the earth.

The treasures themselves are displayed in the British Museum, where the helmet, reconstructed from over 500 fragments, has become an icon of early medieval England.

The Site Today

On site, the National Trust tells the story of the dig and the people behind it…not only kings but also Edith Pretty and Basil Brown, whose persistence made the discovery possible.

Sutton Hoo remains one of the most evocative finds in British archaeology. It bridges myth and history, bringing to life the world of Beowulf, where ships carried warriors to sea and kings were buried with treasures to sustain them in the afterlife.

From the rivets of the ship to the glint of the gold buckle, the site speaks of a society both martial and sophisticated, connected to distant lands yet rooted in the soil of East Anglia.

Eighty years on, Sutton Hoo still captures the imagination. It reminds us that beneath the quiet fields of England, the past waits…sometimes in splendour…for those bold enough to dig.