In the medieval period, bread wasn’t just a food…it was a fundamental part of daily life, a staple that nourished the people of Britain and beyond.

Whether you were a noble sitting in a grand hall or a peasant toiling in the fields, bread was likely to be found at every meal, and the way it was made reflected the resources and status of those who ate it.

In villages and towns, bread-making began with grain, typically wheat, rye, or barley. The grain would be milled by hand or using a water-powered mill, which was the lifeblood of the medieval economy.

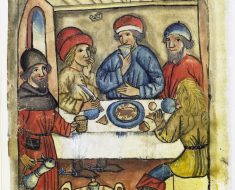

Once the grain was ground into flour, it was mixed with water, salt, and sometimes yeast or leaven. For the higher classes, fine white bread made from finely milled wheat was the height of luxury. This light, fluffy loaf was reserved for kings and nobles.

The lower classes, however, had to make do with rye or barley bread, which was much denser, darker, and often harder to chew. Once the ingredients were mixed into dough, it was kneaded…a laborious process that required strength and patience.

Kneading helped to develop the gluten, giving the bread its texture. In some households, the dough was left to rise slowly, often overnight, to allow the natural yeasts from the air to work their magic. For the wealthy, bread ovens were often part of their estates.

These were wood-fired, massive stone structures that were carefully heated to just the right temperature. Baking bread in these ovens was an art in itself, and the ovens were often used for other food as well. For commoners, however, communal ovens were the norm, where multiple households would pay to bake their loaves.

The process of baking itself could take hours, with the bread needing to be carefully watched to ensure it was cooked just right. Once it was out of the oven, the bread was left to cool, but it wouldn’t last long. Stale bread was a common problem, especially in the warmer months, and many lower-class households would rely on day-old loaves, using them for stews or soaking up sauces from their meals.

Bread had symbolic significance too, especially in Christianity. In church, the breaking of bread became a central part of religious rituals, a symbol of faith and community. It wasn’t just something you ate… it was a sacrament, a link to something greater!

However, bread wasn’t always abundant. The medieval world was at the mercy of the weather, and bad harvests often led to famine. When grain became scarce, bread prices soared, and the poor would sometimes resort to eating bread made from substitute grains like peas or even acorns.

During these tough times, bakers and millers were often heavily regulated by the Assize of Bread to prevent price gouging and to ensure fair distribution.

In towns and cities, bakers often formed guilds to regulate the craft, setting standards for the quality of bread and ensuring it was sold at a reasonable price. These guilds were not just concerned with food safety…they also had a social role, ensuring that bread was available to all, no matter their station.

Medieval bread-making was far more than just a culinary practice; it was woven into the fabric of everyday life, from its role as a basic foodstuff to its place in rituals and traditions. Whether it was a simple, coarse loaf or a luxurious white bread served at a feast, bread in the medieval period was as much a symbol of survival and community as it was a meal. The methods of making it, passed down over centuries, have influenced how we still bake and eat bread today. Now I’m off to get some sourdough and cheese!