The Middle Ages were a period of stark contrasts, and nowhere was this more evident than in the food people ate.

Diets varied dramatically depending on social class, geography, and season, but across Europe, the staples and delicacies of medieval life reveal a culture of both resourcefulness and ritual.

Our Daily Bread

For the majority of people…peasants living in villages and working the land…food was simple and largely plant-based.

Bread was the cornerstone of the diet, often coarse and dark, made from barley, rye, or oats rather than the fine wheat favoured by the wealthy.

Porridge, often mixed with herbs or whatever vegetables were in season, was another common staple. Peasants supplemented these basics with vegetables from small gardens, including onions, leeks, cabbage, and beans.

Meat was rare, eaten only on special occasions or when the opportunity arose to hunt or butcher livestock. Fish, however, was more accessible, especially for those living near rivers, lakes, or the coast, and it was a staple during religious fasting days when meat consumption was restricted.

The Wealthy

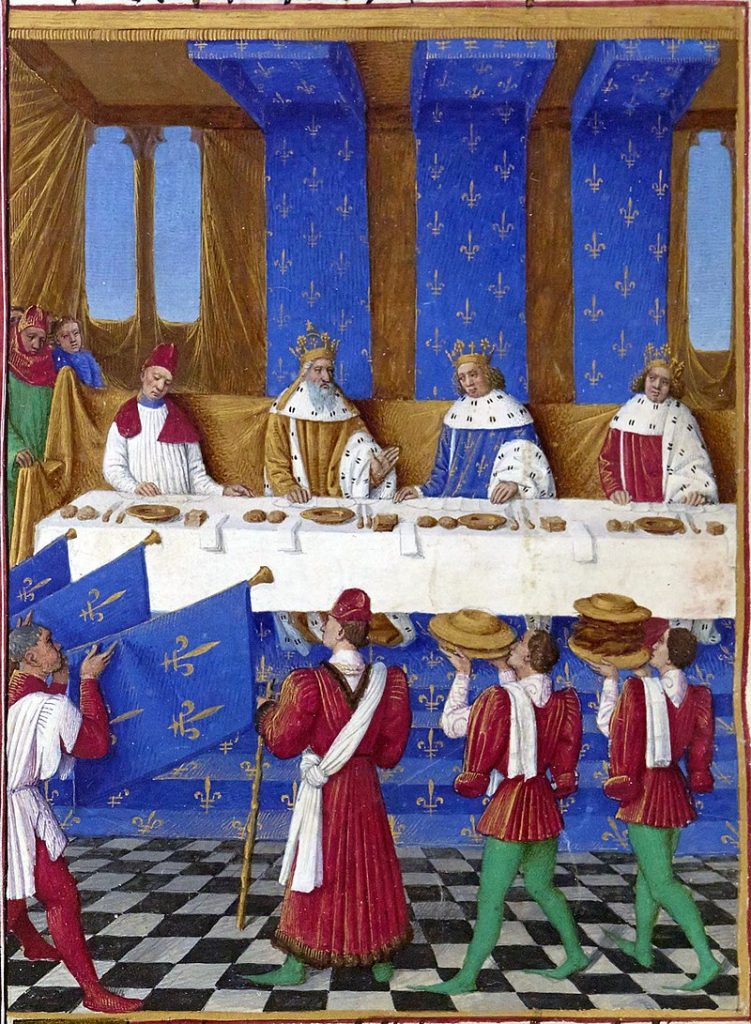

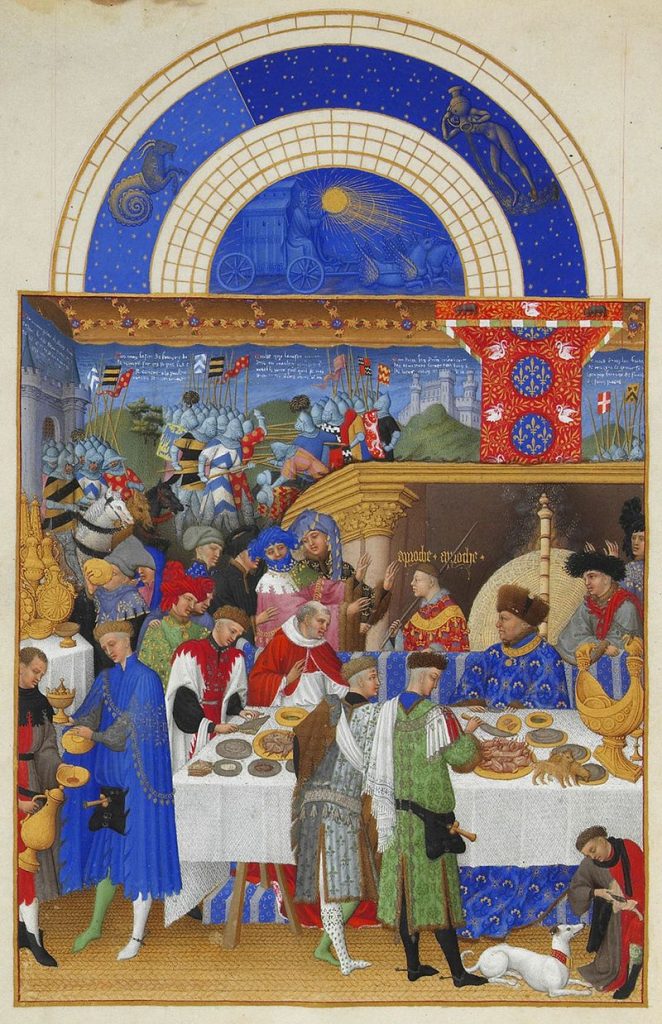

The diet of the medieval elite, in contrast, was far more lavish.

Nobles and royalty enjoyed access to a wide variety of meats, including beef, pork, lamb, venison, and game birds such as pheasant, swan, and partridge.

Their tables also boasted fish from both freshwater and the sea, and they were particularly fond of salted and smoked varieties, which could be stored for longer periods.

Bread remained a staple, but the wealthy consumed it in finer forms made from wheat. Exotic spices like saffron, cinnamon, and pepper were prized additions, imported from the East, and often used as a display of wealth as much as for flavour.

Methods

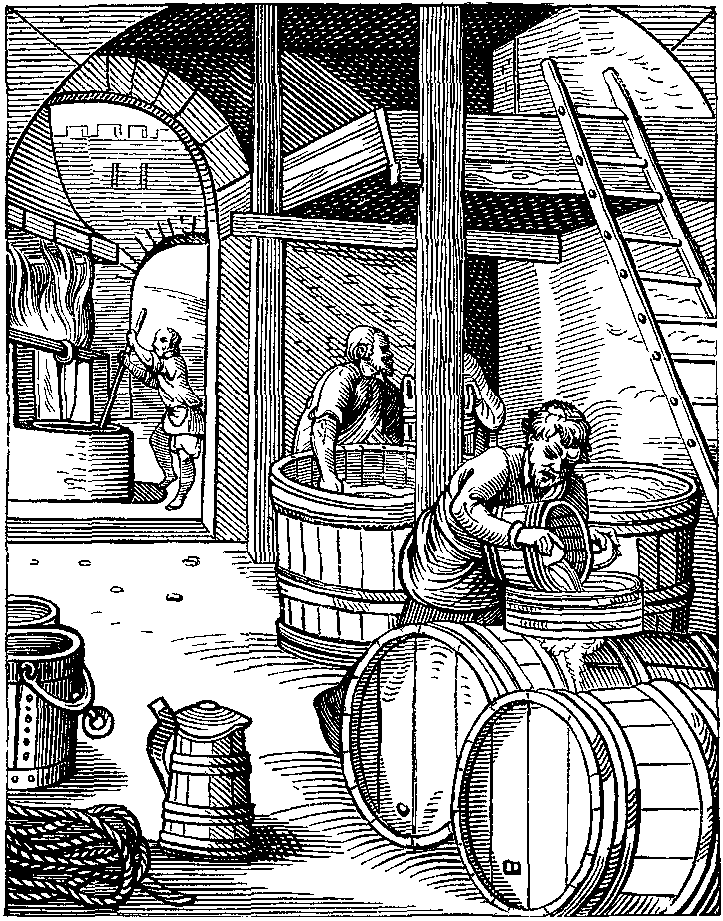

Medieval cooks were also inventive with the preservation of foods.

Salting, smoking, pickling, and drying were essential for maintaining meat and fish through the winter months or on long journeys.

Honey served as the primary sweetener, as sugar was scarce and extremely expensive before the late Middle Ages.

It was used not only to sweeten dishes but also in sauces and meads. Dairy products, including cheese and butter, were common, though their quality and availability again depended on wealth and location.

Seasonality governed much of medieval cuisine.

Markets and home gardens dictated what was eaten day-to-day, with roots and winter vegetables dominating the cold months, while berries, fruits, and fresh herbs were more common in spring and summer.

Pies, tarts, and stews offered a way to combine ingredients efficiently, stretching more expensive foods with grains and legumes.

Dinners on the Table

Meals were also influenced by religious practice. Christianity imposed numerous fasting days, requiring abstention from meat, leading to an increase in fish, legumes, and vegetables on these occasions.

Feasts, in contrast, were occasions for extravagance, with multiple courses, elaborate displays, and dishes designed to impress as much as to satisfy hunger. At grand banquets, presentation was key: gilded pastries, spiced meats, and colourful sauces showcased wealth and sophistication.

Despite the differences between rich and poor, medieval people shared a common approach to food that emphasised practicality and efficiency.

Nothing was wasted; scraps fed animals, and every part of a slaughtered animal found a use in broths, sausages, or preserved meats. Herbs were grown not only for flavour but also for medicinal purposes, highlighting the overlap between nutrition and health in medieval thought.

Cheers!

Beverages were also central to medieval dining. Water was often unsafe to drink, so beer, ale, and wine became everyday staples.

Small children and adults alike drank weak ale, while wine was more common among the elite. Milk was consumed where available, but its perishable nature made it less reliable.

Overall, the foods of the Middle Ages reveal a society shaped by social hierarchy, geography, and religion. While peasants relied on simple, filling foods to sustain them through long days of work, the wealthy indulged in lavish banquets designed to impress and display status.

Preservation techniques, seasonality, and the limited availability of certain ingredients meant medieval diets were seasonal and regional, but always inventive.

Studying these foods gives us a tangible connection to daily life in the past, from the bustling market stalls to the grand feasting halls, and reminds us that what people ate was as much about survival as it was about identity, culture, and community.